How to dive

Scratch

Scratch window is a scratch notebook of code snippets similar to emacs *scratch* buffer.

You can open, close, and save the script file in the buffer.

You can also debug the code in the following step:

-

In Scratch window, select the buffer you want to debug.

-

Pressing [M-j] compiles the code and evaluetes it in the currently selected shell namespace. The code "

" now can be referenced from the debugger of the shell. -

Then, you can debug the code using :ref:

command-hookand :ref:trace-hookas well as the Log window.

Key bindings of Scratch::

C-x C-o : open

C-x C-s : save

C-x S-s : saveas

C-x C-l : load

C-x C-k : kill-buffer

C-x k : kill-all-buffers

C-x C-n : new-buffer

M-j : exec-buffer

C-j : eval-line

Magic syntax

Nautilus shell accepts some magic syntaxes e.g.,

>>> x`y

# interpreted as (quoteback):

# ==> y=x

>>> x@y

# interpreted as (pullback):

# ==> y(x)

For example,

>>> 5 @range @list @p

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

In Ruby, one of the popular programming languages, you can chain methods like this:

irb> p 5.times.to_a

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4]

Note that in contrast of Ruby, it can also chain p (print) function.

Actually, it can chain not only methods but also any functions as follows:

>>> buf @io.BytesIO @Image.open @np.asarray @plt.imshow; plt.show()

# interpreted as:

==> plt.imshow(np.asarray(Image.open(io.BytesIO(buf)))); plt.show()

.. seealso::

The name "pullback" comes from mathematical terminology.

Pullback is like a mathematically defined synonym of substitution.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pullback

Built-in utilities

Nautilus has some useful functions in builtin module::

@p Synonym of print.

@pp Synonym of pprint.

@info Short info.

@help Full description.

@load Load file in Log buffer.

@where Displays filename:lineno or the module name.

@mro Displays mro list and filename:lineno or the module name.

@dive Clone the shell with new target.

@debug Open pdb or event-monitor.

@timeit Measure the duration cpu time (per one execution).

@profile Profile a single function call.

@filling Inspection using ``wx.lib.filling.Filling``.

@watch Inspection using ``wx.lib.inspection.InspectionTool``.

p(print) / pp(pprint) / filling

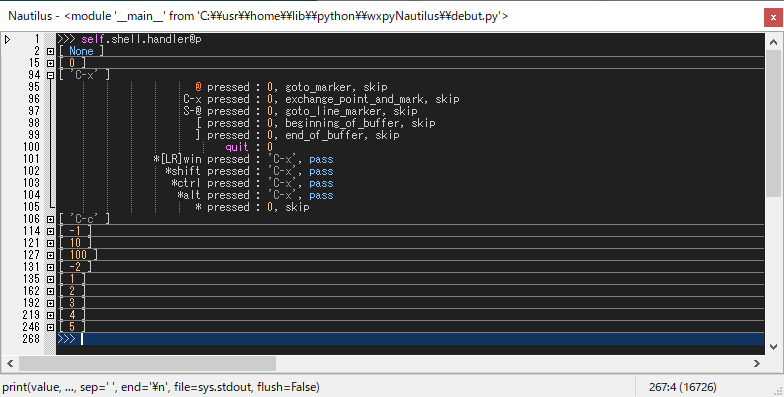

>>> self.shell.handler @p

# Display shell key bindings.

The special object handler is like DNA, defining how the object interact in a process. In fact, it is a simple dictionary of Finite State Machine (FSM) that maps states to transitions and actions.

In this case, ['C-x'] state has the key-event ['@ pressed'], thus two-stroke typing [C-x @] invokes goto_marker which moves the caret to the marker (o) position.

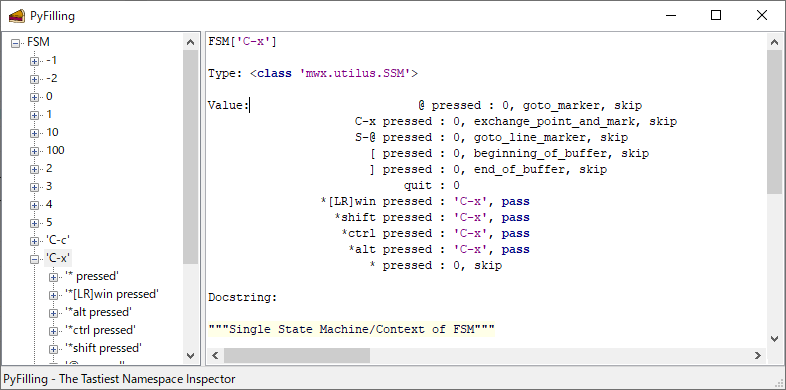

You can also use fancy view of the key bindings using PyFilling window.

>>> self.shell.handler @filling

# Show shell key bindings in ``PyFilling`` window.

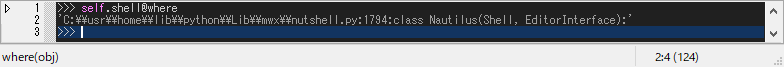

where / load / mro

The command where is used to find the source code.

>>> self.shell @where

# Displays the source code filename:lineno.

Default Log window can be used to open the file.

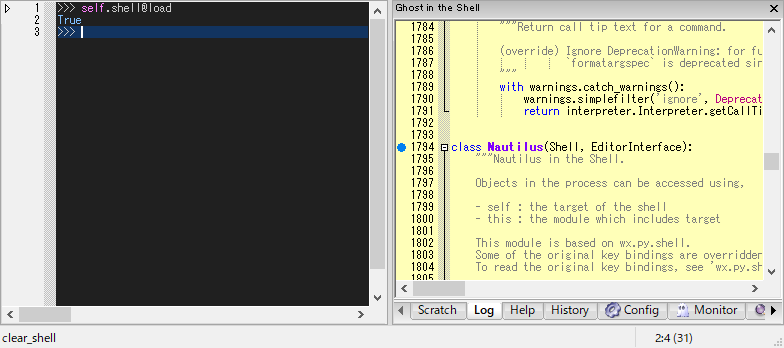

>>> self.shell @load

# Loads the source code in **Log** window.

If you like to open the file with your editor, define a function edit('filename:lineno') somewhere such as 'PYTHONSTARTUP' script file. Then, you can open the file like this:

>>> self.shell @where @edit

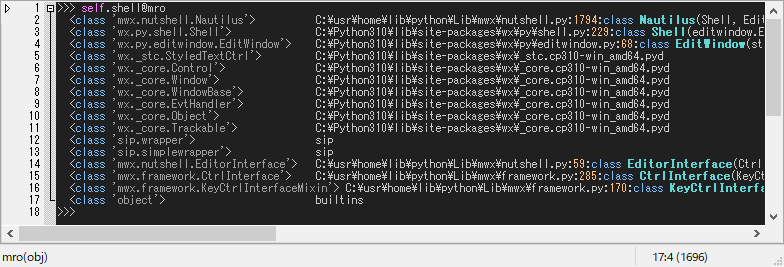

The command mro displays mro list of the object with filename:lineno.

You can grep those files if exist, using [f10]: grep-forward, [S-f10]: grep-backward.

>>> self.shell.handler @mro

# Displays mro list and filename:lineno or the module name.

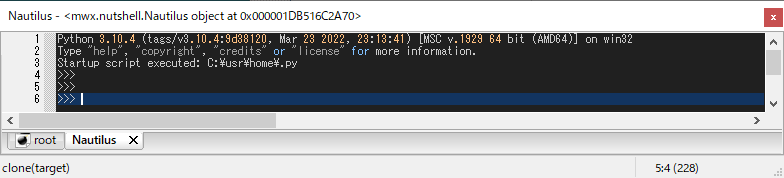

dive

The command dive is equiv. to rootshell.clone which creates a new shell with the specified target in the new page.

>>> self.shell @dive

# Clone the shell with the specified target.

# In this case, that target is the ``rootshell<Nautilus>`` itself.